How Cognitive Biases Affect Decision Making In Product Development

Welcome Back, Product Enthusiasts! 👋

Wow, last month’s response to “How to Turn Users into Growth Engines?” absolutely blew me away! Your stories about building growth engines and getting users to champion your products were downright inspiring. Honestly, they made my week.

But something kept nagging at me after that newsletter. While reading your feedback and reflecting on my own product journey, I realized how often hidden biases creep into our decision-making - even when designing something as seemingly objective as a viral loop.

I’ve seen it myself: a promising idea overshadowed by confirmation bias, or a brilliant team stuck in the sunk cost fallacy.

It reminded me of a tough decision I once had to make about killing a feature we were emotionally attached to. It felt wrong at the time, but ultimately, it saved the product. That moment got me thinking - how many of our best-laid plans are quietly sabotaged by the way our brains are wired?

So, this week, I’m diving headfirst into a topic that feels deeply personal and crucial: how biases shape - and sometimes derail - our most critical decisions.

What You’ll Learn Today 📚

The hidden dangers of cognitive biases in product development.

Real-world case studies of companies that fell prey to these traps - and those that broke free.

Practical frameworks to identify and counter biases.

Tools and techniques to improve your decision-making processes.

To kick things off, let’s revisit one of the most pivotal moments in tech history - a story of confidence, miscalculation, and lessons in humility 🤯

The Hidden Psychology Behind Product Failures

It's January 2007, and Steve Ballmer, Microsoft's then-CEO, is being interviewed about Apple's newest product - the iPhone. With a confident laugh, he declares:

"There's no chance that the iPhone is going to get any significant market share. No chance."

But here's what makes this story fascinating - Steve Ballmer wasn't just shooting from the hip. Microsoft had conducted extensive market research. They had decades of mobile device experience with Windows Mobile. They had data showing that business users (their primary market) preferred physical keyboards.

So what went wrong?

This is where our journey into cognitive biases begins.

Over the next 10 minutes, I'm going to take you deep into the psychology behind product decisions, sharing stories you've never heard before, backed by research, and providing practical techniques you can use immediately📌

The Most Dangerous Cognitive Biases in Product Development

First, what exactly is a COGNITIVE BIAS?

Cognitive biases are like invisible architects of our thoughts. They're mental patterns that help us process information quickly, but can also lead us astray. Think of them as shortcuts our brain takes to make faster decisions - useful for surviving on the savannah thousands of years ago, but sometimes problematic when making complex business decisions in today's world.

Remember Ballmer's confident dismissal of the iPhone I talked about above? That story illustrates how even the smartest business leaders can fall prey to cognitive biases - those mental shortcuts and predispositions that silently shape our decisions, often without us realizing it.

What went wrong was a perfect storm of cognitive biases that plague even the most experienced business leaders:

The Curse of Knowledge: Microsoft was trapped by its own expertise. Having dominated the business mobile market for years, they couldn't imagine a world where consumer preferences would dramatically reshape business technology. Their deep understanding of their existing customers became a blindspot.

Confirmation Bias: Microsoft's market research focused heavily on existing business users who, predictably, confirmed their preference for physical keyboards. They found exactly what they were looking for - validation of their existing worldview.

Status Quo Bias: The company was viewing the future through the lens of their past success. Physical keyboards weren't just a feature - they were Microsoft's competitive advantage in the mobile space. Letting go of this would mean admitting their existing strategy might be wrong.

The irony? Ballmer and Microsoft's confident dismissal of the iPhone wasn't despite their experience and data - it was because of it. They had fallen into what psychologists call the "Expert Trap" - where expertise in one paradigm makes it harder to recognize paradigm shifts.

By 2012, just five years after Ballmer's infamous quote, the iPhone had revolutionized not just the consumer market, but the business world Microsoft thought they understood so well. The physical keyboard, once seen as essential, became a relic.

The lesson? Sometimes our greatest strengths - our experience, our data, our expertise - can become our greatest weaknesses if we let them blind us to transformative change.

Success in product development isn't just about knowing your market - it's about being willing to question everything you think you know about it.

Now that we understand how cognitive biases can blind even industry giants like Microsoft, let's dive into the most dangerous of these mental traps that lurk in product development - and more importantly, how to spot them before they derail your next big project.

Confirmation Bias: The Silent Product Killer

Imagine you’re shopping online for a pair of running shoes. You’ve already decided on a brand - let’s say Nike. As you scroll through reviews, you notice something interesting: you skim past negative feedback but linger on the glowing reviews, nodding in agreement.

Now, here’s the twist—those negative reviews might have valid points, but you don’t want to see them. Your brain is subconsciously filtering information to validate your initial choice. This is confirmation bias at work.

First identified by English psychologist Peter Wason in 1960, confirmation bias is our tendency to seek out and prioritize information that aligns with our beliefs while ignoring evidence to the contrary. Wason’s experiments, like the famous Wason Selection Task, revealed how deeply ingrained this bias is in our thinking - even when solving simple logical problems.

In his bestselling book "The Design of Everyday Things" (2013), Don Norman shares a profound insight: "The most dangerous part of confirmation bias isn't that we seek confirming evidence - it's that we don't realize we're doing it."

Let's look at one of the most stunning examples in tech history: Nokia's response to the iPhone.

The Nokia Story: A Deeper Look

In 2007, Nokia commanded 49.4% of the global mobile market. They were more than a market leader; they were the market. The company's internal documents, later revealed in Risto Siilasmaa's book "Transforming Nokia" (2018), show something fascinating:

Nokia's research team had actually developed a working touchscreen prototype in 2004. But here's where confirmation bias kicked in spectacularly. The team conducted user testing with existing Nokia users and found that:

82% preferred physical keyboards

67% found touchscreens "less efficient"

71% said they wouldn't buy a phone without physical buttons

Sounds convincing, right? But there was a crucial flaw in their research.

Dr. Anirudh Dhebar, in his 2016 paper "Nokia's Fall from Grace" (published in the Harvard Business Review), reveals that Nokia's research:

Only tested with existing Nokia users

Focused on immediate user reactions rather than learning curve potential

Compared their prototype to existing physical keyboards rather than testing potential improvements

As Timo Vuori, former Nokia executive, shared in his 2019 interview with McKinsey Quarterly: "We were essentially asking people who had never used a touchscreen if they would prefer something they'd never experienced over something they'd used for years."

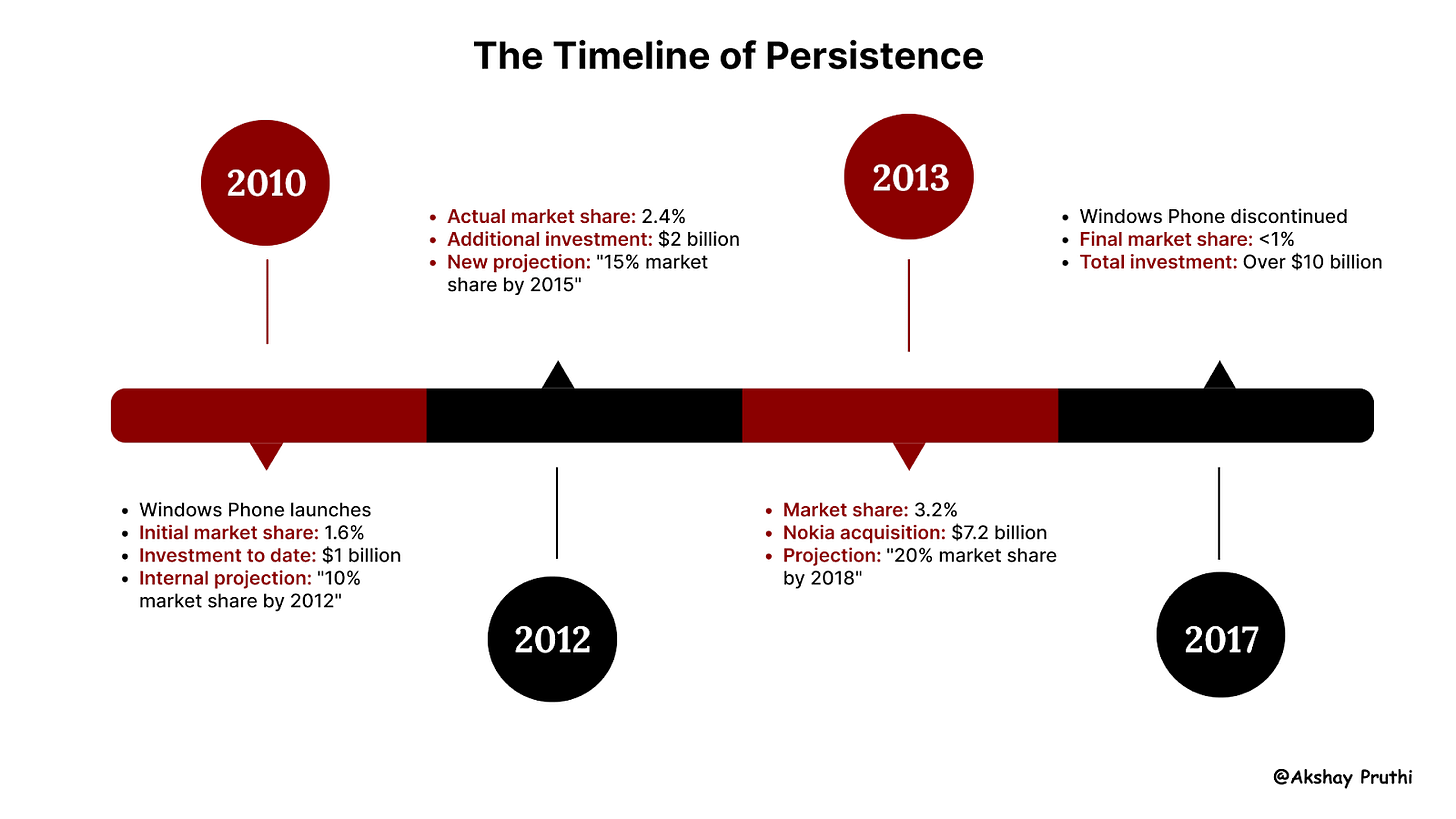

The Sunk Cost Fallacy: Microsoft's $7.2 Billion Lesson

Picture this: you’re at a movie theater, 30 minutes into a film you’re not enjoying. The plot is dull, the characters are flat, and you’re checking the time every few minutes. But instead of leaving, you stay. “I already paid for the ticket,” you tell yourself. “I might as well see it through.”

Sound familiar? That’s the sunk cost fallacy - the tendency to continue investing in something simply because you’ve already spent time, money, or effort on it.

This bias was first described by economists Richard Thaler and Daniel Kahneman, who showed how loss aversion often leads people to throw good money after bad.

Here's a number that should make every product manager pause: $7,200,000,000. That's how much Microsoft spent acquiring Nokia's phone business in 2013, long after it was clear that Windows Phone was struggling.

Let's dig deeper into this fascinating case study.

In his 2019 book "Hit Refresh," Satya Nadella reveals something fascinating about Microsoft's internal discussions during this period. The company had quarterly "reality check" meetings where teams would present data about Windows Phone's performance. But here's the twist - each meeting focused not on whether to continue, but on how much more to invest.

Dr. Daniel Kahneman, in his 2011 book "Thinking, Fast and Slow," explains this behavior perfectly: "The sunk cost fallacy keeps us in a losing game long after it's clear we should exit, simply because we've already invested so much."

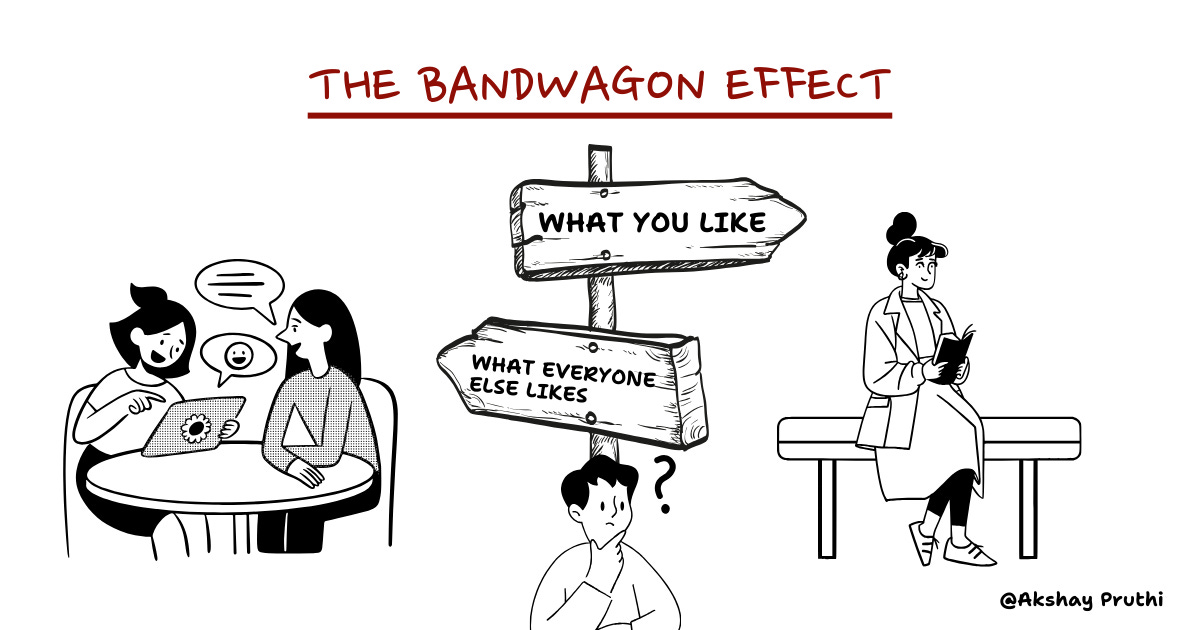

The Bandwagon Effect: The Great Audio Chat Gold Rush

Have you ever joined a new social media platform just because all your friends were on it? At first, it seems exciting - everyone’s talking about it, and you don’t want to be left out. But after a few weeks, the novelty wears off, and you stop using it altogether.

This is the bandwagon effect - our tendency to adopt ideas, trends, or products simply because others are doing it. It’s driven by social proof, the psychological phenomenon where we assume the popularity of something equates to its value.

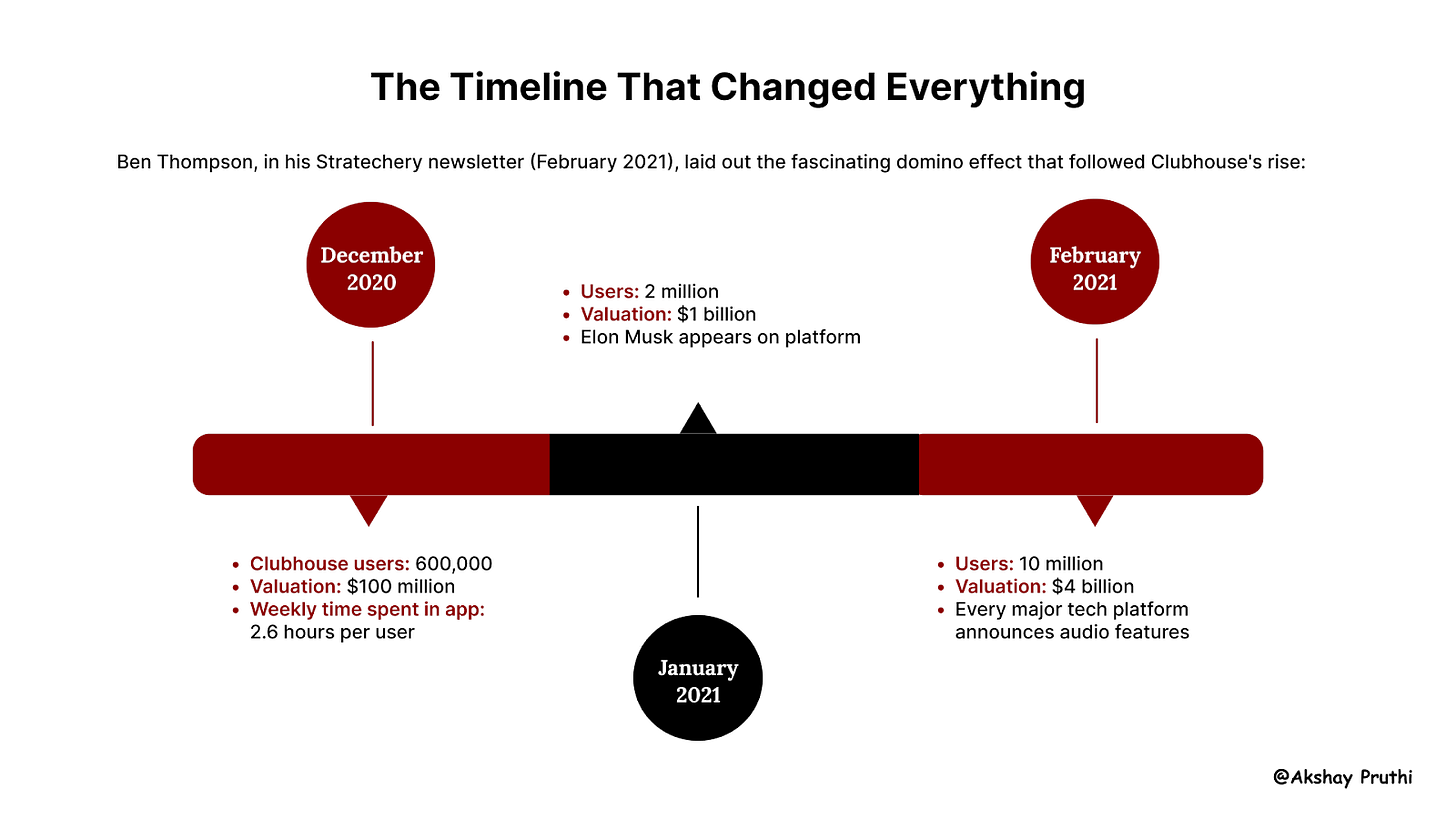

Remember Clubhouse? Let's dive into what might be the most expensive case of "me too" product development in recent history.

What happened next is a masterclass in the bandwagon effect.

Casey Newton, in his Platformer newsletter, obtained internal documents from several major tech companies showing their audio feature development timelines. The fascinating part? Not a single company had significant user demand for audio features before Clubhouse's rise.

A former Twitter product manager (speaking anonymously in The Information's report) revealed: "The conversation wasn't 'Do our users want this?' but 'How quickly can we ship it?'"

The Results:

Twitter Spaces: Less than 1% of Twitter users actively hosting spaces by 2023

Facebook Live Audio Rooms: Discontinued in 2022

Spotify Greenroom: Shut down after $62 million investment

LinkedIn Audio: Never left beta

Professor Scott Galloway, in his 2023 book "Platform Power," estimates that major tech companies collectively spent over $500 million developing Clubhouse clones. Most were abandoned within 18 months.

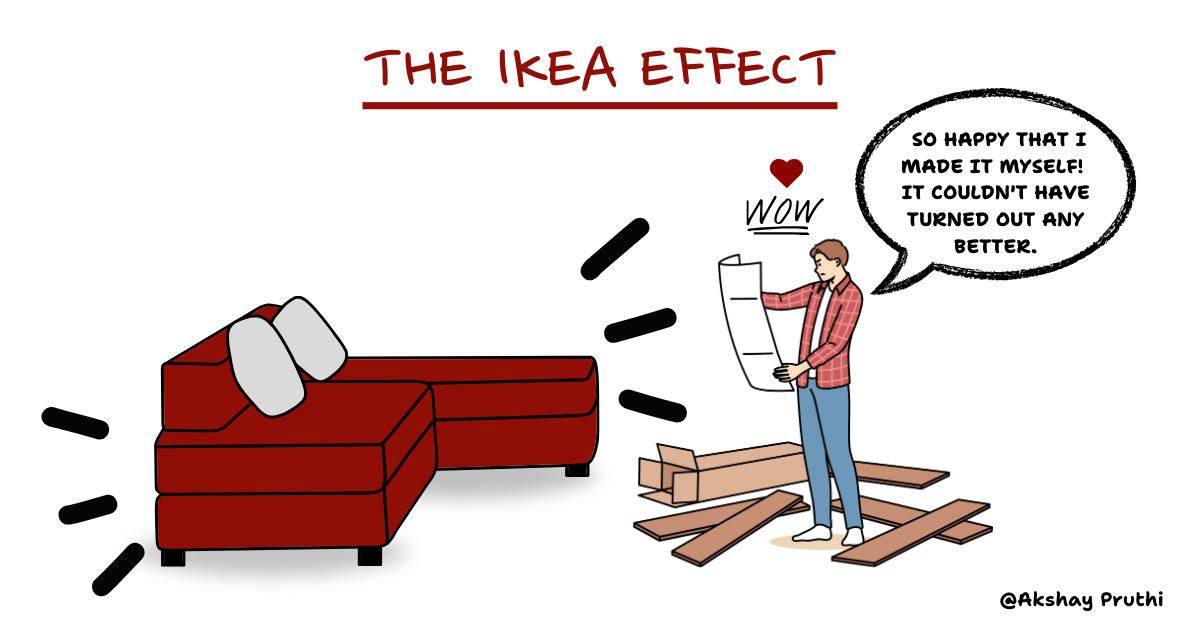

The IKEA Effect: When Love Blinds Us

Now imagine this: you spend hours building a piece of furniture from IKEA. The instructions are confusing, you struggle to align the pieces, and you accidentally strip a few screws. When you’re done, the result is far from perfect. But despite its flaws, you’re weirdly proud of it.

This is the IKEA effect - our tendency to overvalue things we’ve created ourselves. First identified by Michael I. Norton in 2012, experiments showed that people were willing to pay more for self-assembled products than for identical pre-assembled ones.

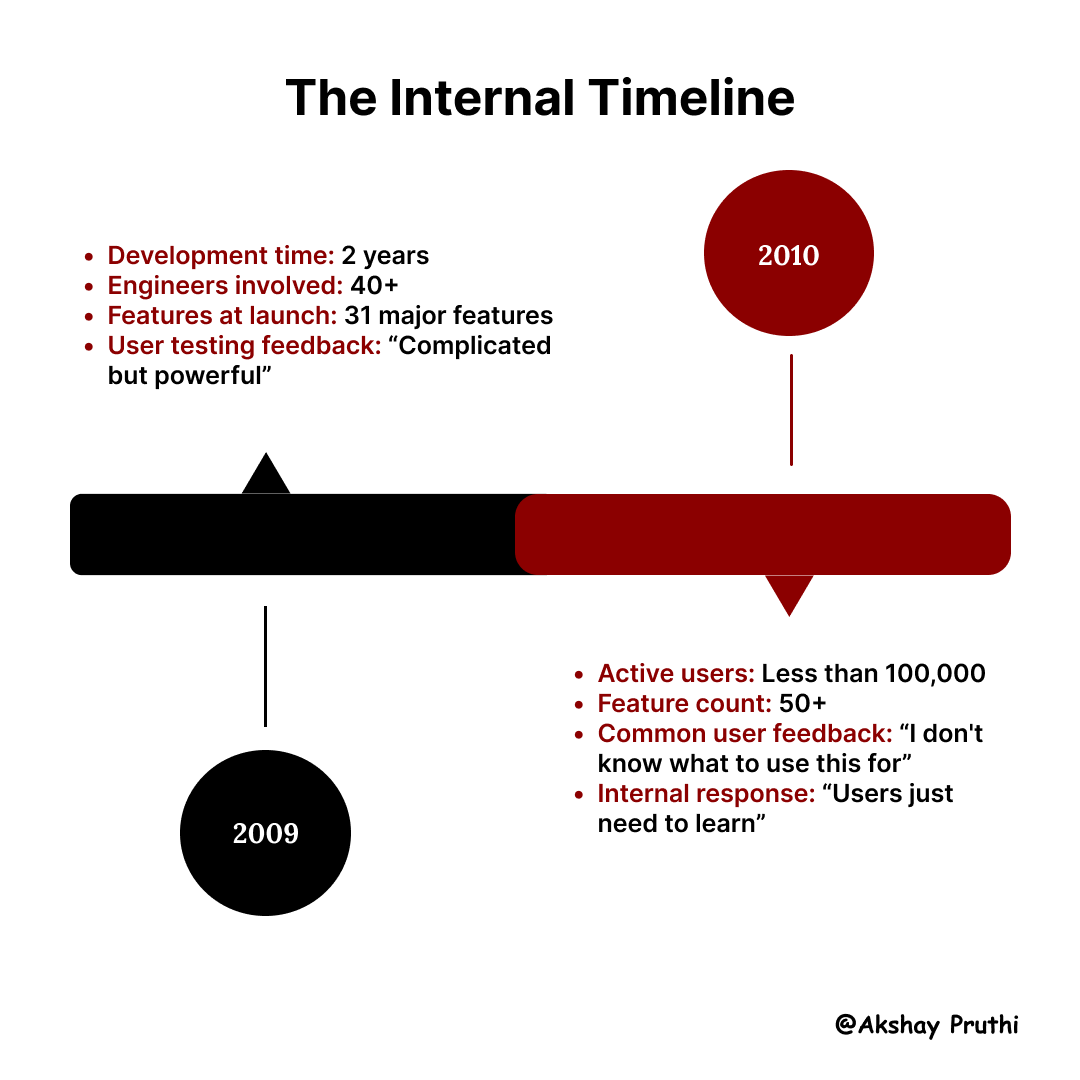

Google Wave: A Love Story Gone Wrong

Let's dive into one of the most fascinating product failures in Google's history.

Lars Rasmussen, Wave's creator, gave a revealing talk at Web 2.0 Summit in 2010. He shared something that perfectly illustrates the IKEA effect: "We were so in love with the complexity of what we'd built, we couldn't understand why users found it confusing."

Dr. Teresa Torres, in her book "Continuous Discovery Habits" (2021), uses Google Wave as a prime example of the IKEA effect in product development. She points out that the team had become so invested in their creation that they:

Interpreted user confusion as user error

Saw complexity as sophistication

Viewed learning curve as a feature, not a bug

Now comes the most important part - how do we actually fight these biases? 🪜

Breaking Free from Cognitive Biases

I've spent months researching and interviewing product leaders about their practical approaches. Here's what really works 💡

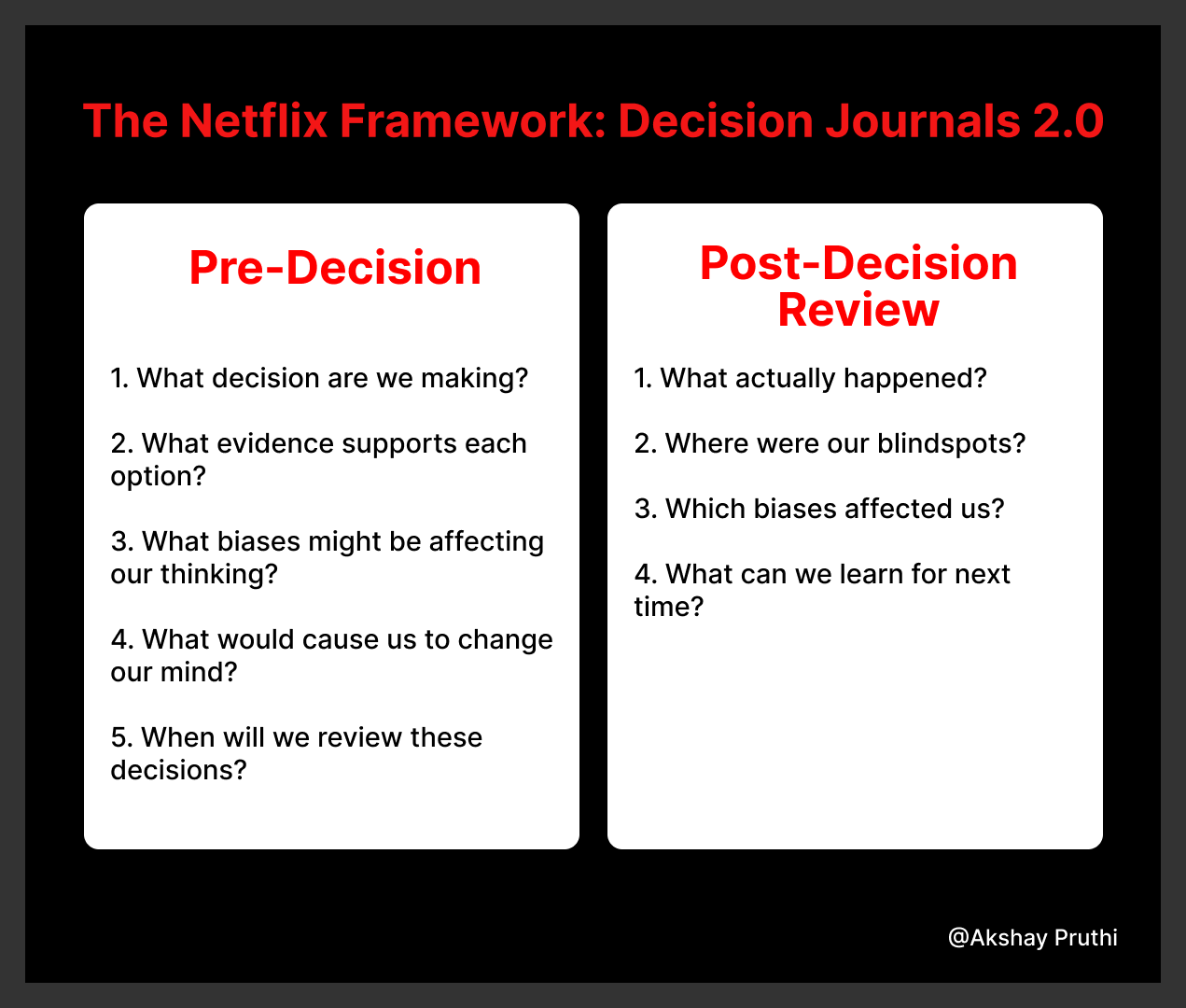

1. The Netflix Framework: Decision Journals 2.0

Gibson Biddle, former VP of Product at Netflix, recently shared their evolved decision-making framework in his "Ask Gib" newsletter. It's fascinating because it goes beyond simple documentation.

2. The Pre-Mortem Framework: Anticipating Failure Before It Happens

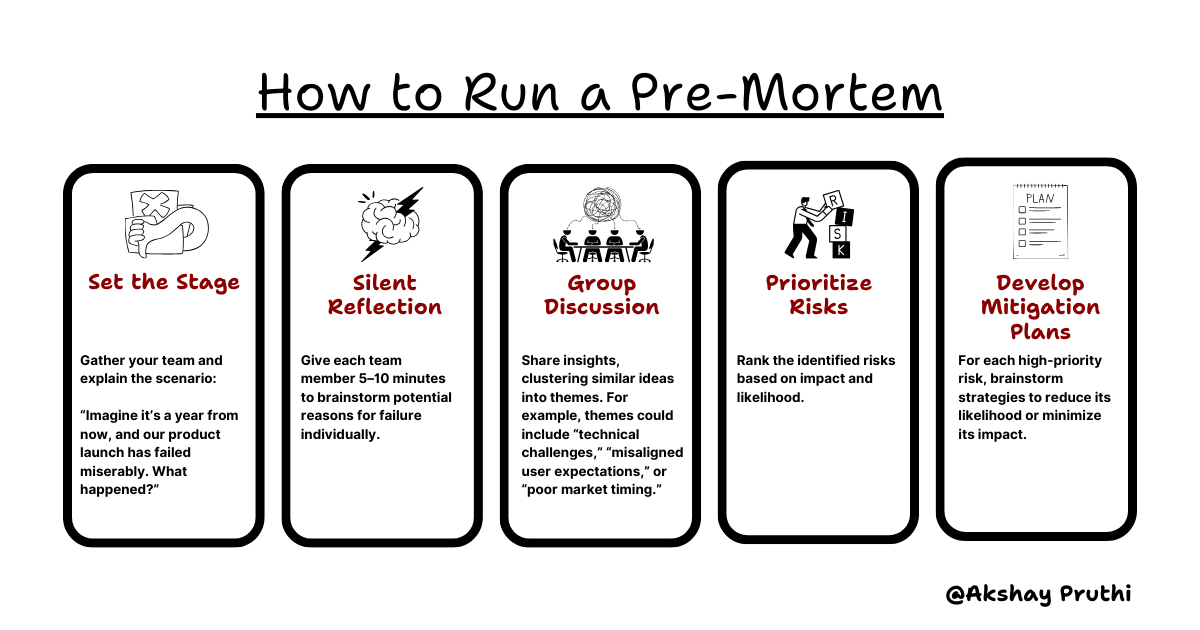

Psychologist Gary Klein popularized the pre-mortem technique, a method where teams imagine their project has failed spectacularly and then work backward to identify why it went wrong. This proactive approach surfaces potential pitfalls that traditional brainstorming often misses.

Example: Spotify’s Pre-Mortem for Podcasts

When Spotify decided to invest heavily in podcasts, they ran pre-mortems to explore what could go wrong. Key risks identified included:

Content creators opting for YouTube over Spotify.

User fatigue from too much ad insertion.

Poor discoverability of niche podcasts.

These insights led Spotify to focus on exclusive creator deals, personalized podcast recommendations, and ad frequency controls. Today, Spotify is one of the biggest players in podcasting, with over 100 million podcast listeners globally.

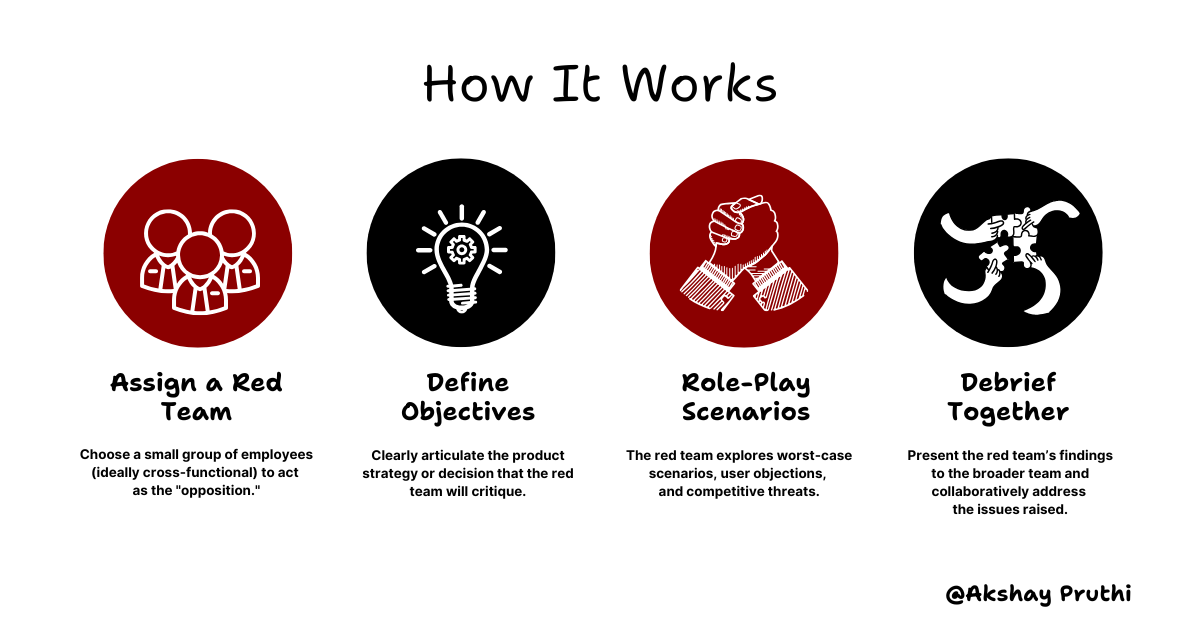

3. The Red Team Exercise: Challenging Your Own Assumptions

The red team exercise, borrowed from military strategy, involves assigning a group to critique and challenge the assumptions of your primary team. The goal isn’t to be combative but to expose blind spots and vulnerabilities.

Example: Amazon’s Use of Red Teams

Amazon famously uses red teams to evaluate the potential weaknesses of their product ideas. When developing the Echo, a red team was tasked with identifying reasons why customers might reject a voice assistant. Their feedback led to a sharper focus on user privacy, resulting in features like the “mute” button that disables the microphone.

Cognitive Biases in Action – A Success Story

Let’s wrap this up with a story that perfectly captures how a company identified its blind spots, tackled its biases, and turned a good idea into a billion-dollar cultural phenomenon.

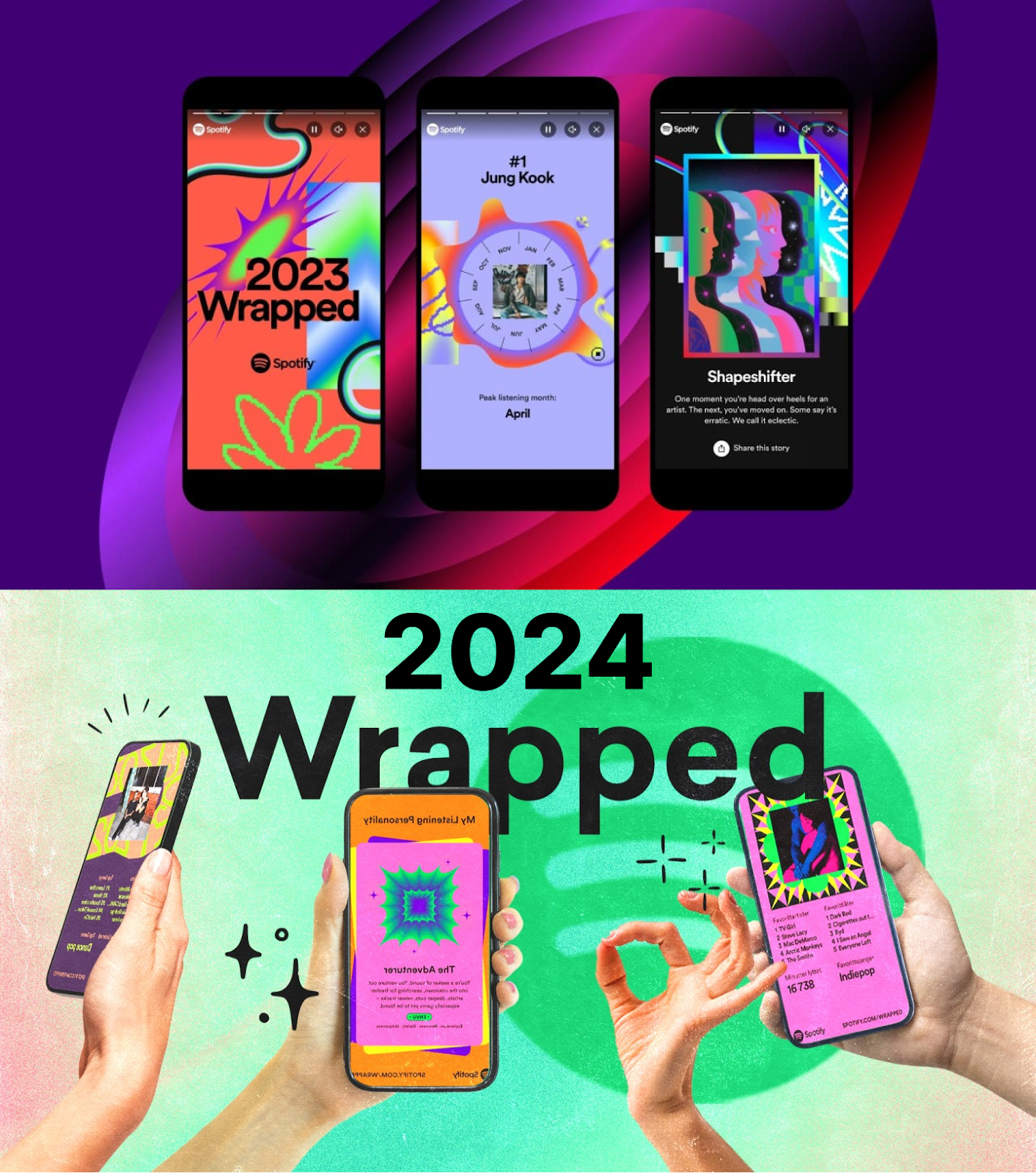

Every December, millions of Spotify users eagerly await their Wrapped - a personalized summary of their year in music. It’s fun, it’s colorful, and it’s everywhere on social media. For Spotify, Wrapped isn’t just a feature; it’s a celebration of their brand and a cornerstone of their customer retention strategy.

But here’s what you might not know: Wrapped wasn’t always this polished or popular. In its early days, the concept was underwhelming. Some users didn’t see the point. Others found the format too complicated, with overwhelming visuals and insights that felt more like data dumps than engaging stories.

Spotify could’ve easily fallen into the trap of confirmation bias, telling themselves, “It’s great as it is—users will come around eventually.” Instead, they went back to the drawing board, armed with a set of frameworks designed to counteract cognitive blind spots.

The Early Struggles

When Wrapped first launched, it didn’t immediately resonate. Some users loved it, but many others didn’t share their results, which was a key goal for Spotify. Internal teams debated why. Was it too complex? Did users feel uncomfortable with the amount of data being shared? Or was it simply not engaging enough?

To find answers, Spotify’s product leaders leaned into pre-mortem analysis. They imagined the worst-case scenario: Wrapped failing to gain traction and users disengaging entirely. From there, they worked backward, brainstorming every potential issue. One risk stood out: the fear of being “spied on.” Wrapped was built on personal data, and if users didn’t feel in control, it could backfire spectacularly.

This realization led to an immediate shift. Spotify simplified the visuals and added messaging to reassure users about privacy.

Instead of “look at everything we know about you,” the tone became celebratory: “This is your year in music!”

Wrapped wasn’t just about data; it was about making users feel special.

Challenging Assumptions

Even after these changes, some doubts lingered. Would users actually share their Wrapped publicly? Internally, a red team was assembled to poke holes in the strategy. Their argument? Most people wouldn’t want to broadcast their listening habits. Sharing playlists or albums was one thing, but revealing how many hours you spent listening to lo-fi beats to focus might be a step too far.

This critique sparked a breakthrough. Instead of relying on users to share their entire Wrapped report, Spotify introduced customizable share cards, highlighting fun, non-intrusive stats like “Your Top Artist” or “Your Most Played Genre.” These cards were optimized for social platforms like Instagram, making them easy - and irresistible - to share.

Listening to Users

Wrapped’s success wasn’t just a result of internal brainstorming. Spotify made continuous discovery a priority, scheduling weekly interviews with users to understand what worked and what didn’t.

These conversations revealed an unexpected insight: users weren’t just interested in their personal stats. They wanted to see how their listening habits were compared to others. Were they in the top 1% of Taylor Swift fans? Did their favorite genre match global trends?

Spotify took this feedback and ran with it, adding new features like “Your Artist Rank” and comparisons to broader listening trends. These tweaks transformed Wrapped from a private summary into a social, shareable experience that tapped into users’ sense of identity and community.

From a Feature to a Phenomenon

Today, Spotify Wrapped isn’t just a product - it’s an event. Every December, timelines light up with colorful infographics and personalized playlists, turning Spotify into the center of the cultural conversation.

For users, it’s a moment of reflection and fun. For Spotify, it’s a masterclass in brand loyalty and user engagement.

And it all happened because Spotify wasn’t afraid to confront its own biases, challenge assumptions, and listen - really listen - to its users.

So the next time you’re building a product, think about Wrapped.

Think about the risks Spotify took, the blind spots they uncovered, and the frameworks they used to turn a good idea into something extraordinary. And remember: even the best ideas can get better when you’re willing to question them.

Building Products Without Blinders

Cognitive biases are a double-edged sword. They’re an inherent part of being human, but they don’t have to dictate your product decisions. By adopting frameworks like pre-mortems, red team exercises, and decision journals, you can create processes that minimize the influence of biases and prioritize user needs.

Remember: The best product decisions aren’t made in isolation. They’re the result of rigorous questioning, diverse perspectives, and a willingness to challenge assumptions.

So, the next time you find yourself in a meeting, ask:

Are we solving for the user - or for ourselves?

Have we considered what could go wrong?

Are we open to being proven wrong?

The answers to these questions could shape not just your product, but its place in the world.

Here’s to smarter decisions and better products,

Akshay